The Erratics

-

I pick up a lump of chalk and turn it around.

I stare into the white of the screen for far too long, uncertain what to write.Core

The first word written in the empty journal I took with me to the Western Desert. -

Sitting in the ‘Englishman’s House’ – a collapsed lookout post from the last World War, which I’d mistaken for a natural rock formation rather than the broken strips of wall I found left standing like a brick ribcage above the Farrawh Oasis – I wrote the word core in pencil, followed by the line ‘is there a core to the work?’ In my handwriting core looks more like cove – a sheltered, recessed place or a hollow. At the point of writing there wasn’t really any work to speak of, so perhaps a hollow at the core was more accurate, and with no work to surround a core – which might be a hollow – the question negates itself. I’d scribbled it out.

Trying to find words to fit an intention seems – looking back – to have already grasped its end, though sitting there in the rubble of the recent past, thinking about beginning from inside something’s ruin, I didn’t know that then.How do you start something. You begin. The word core (possibly cove) in pencil on an empty page, and then you digress and you misstep and you reorient, but at least you’re moving. There are tipping points where the fragility of a thought shifts into reality, moments that set the imagined into the actual.

-

Words are a starting point and at least erode the emptiness, on the page like they do in life, pouring in and accumulating one after another. Though between every word the emptiness still shows through.

It’s the kind of space things start in, and the kind of space they can die in too. I’ve smothered beginnings for less than their frailties – they’re always tentative and weak, each crawling over the body of the last; it’s my fear, rather than their form, that stills them. I need to trust just one of them, give it the chance to find feet and drag itself ashore, gasping – one realisation that denies all others. Not the survival of the fittest perhaps, but a mutation preserved because something eventually has to be; one thing has to live at the expense of the rest. One thing has to stop beginning and start ending.I took an old camera into a much older desert where the rocks are made of chalk and crumbling.

-

A rock is both an end and a beginning, a forming and an eroding. Its shape is complex, indescribable even. Its past is present, drawn as pattern across its sides and lined in the cracks that foretell its future; fault-lines a weakness shot through the mass like ruin embedded. Each surface is a wound forced by fracture, scarred from whatever body it split apart from. And those – the ones still standing – mark everything lost, like tombstones to themselves, collapsing slowly in a wasteland of their own bones.

I picture the rock itself as a photograph, a surface of time stilled not in the moment of the shutter click, but seemingly so to the moment that is a life.

And then a photograph of a rock is an image of an image of time.

Or let writing make an image of time, of chalk forming when the world was still a sea: single-celled algae floating on its surface form shell-like skins within their bodies and in death shed them sinking, countless millions of tiny skeletons spiralling down through the darkness to the bed below, where they endlessly pile, bone on bone. The weight of an ocean silently crushes them together.

And then the ocean dries up.Then.

How can one word, like one image, contain that much time?An entire ocean dries up – dries into life as a desert; the canyons where monsters swam are sucked dry by a sun whose breath starves the living and scrapes the rocks to dust.

-

I pick up a lump of chalk where it’s lain on the studio floor these past months, salvaged from the foot of the cliffs along England’s South Coast – chosen, if you like, though back then for reasons as slight as my ability to carry it. I hold it before me, the light spreading pale shadows along its ridges, and I close one eye, looking as the lens will at its form and imagining where I might cut.

Chalk is soft enough to carve with a razor-blade, to smooth with sandpaper.I think about how much time can be experienced compared to how much can be compressed or contained.

In one shutter click.

Then: one word.

One gesture – I take a razor to the chalk and with every pass of my blade scrape lifetimes into air. -

Why bring words into this.

Images are sealed to their own past, an inertia that words resist with life. Words rouse in the moment of their reading, always forcing a present:I slide my finger over a surface (there is chalk dust everywhere).

I take a blade to the stone, I cut a straight line.

I write, I write.

But mostly I delete and these words will be only a remainder of the countless others erased, the many that don’t accumulate: no piling up of discarded lines, no sedimentary weight whose surface hides the congealed and deleted mass beneath. They’re just gone.

But beginnings are cheap with words. Unlike the chalk there need be no end to this recurring on-screen white, this continual new-document beginning. The carving is different: there is no going back. To correct a mistake is to cut away more, to redress an imbalance is to dig further in. You can only take away; it gets less and less and it ends in nothing.

Like these rocks blowing into the sand inevitably will. Like I fear my own memories of their presence inevitably will, as repeated exposure to these photographs erodes them too.

-

Memories seem so submissive, the image so quick to supplant.

A further reason for words perhaps – as a means of recovery, seeking out what photographs replace; what work, in its final form, forgets.

For instance –

After hours on the road we simply turned off into the sand. No warning, no sign that I saw, we were just driving across the desert and heading towards nothing that I could see.

I went to the desert without really knowing it was a beginning at the time. I went in part because I couldn’t find any further beginnings at home. My own way of working had closed in around me and I felt as if I had reached a form of paralysis; any subject, any object that might be photographed seemed too laden with form, too connected to a ceaseless stream of associations and interpretations. The desire to be freed from this weight of meaning yet somehow true to the essence of photography had resulted in increasingly restrictive months in the studio, shooting ever simpler blocks and lines. I’d worn away a type of freedom photography offers, a type of encounter with a waiting world.

-

The ground dipped down beyond a ridge and then it was like everything I’d seen from the road those past hours sort of fell away, like one familiar image fading to be replaced by another, but one taken in a different time on an old, discontinued film-stock, washed out and colour-cast. A shade like the stain of the missing ocean spread blurring over everything. Stone rose silently through the sand; rock smudged up into a sagging sky where the pale edges of clouds unwound. All around were white smears, swathes of chalk cresting out of sand in the shapes of water, stilled now as stone.

We stopped on a slope. My guide waited, as he seemed content enough to do then and in the days following, in the shade of the jeep, earphones in. I went on a short way until the ground flattened out and I was alone, and suddenly overwhelmed. I’d not anticipated – how could I – what that amount of silence would sound like: it sounded like nothing. Like a nothing so absolute I honestly felt afraid.

Beyond the reach of an image, some things – the sound of my footsteps in the sand and literally nothing else – are touched only by words, wrapping them around a memory like a body wraps around a life so it isn’t entirely lost to time. But whatever freedoms I insist on ascribing words are just as compromised in writing as the memories I send them to claim: each capitulates to a whole that in becoming one thing forgoes all others as the tangled mess of what was once real is stripped down into the lines chosen to tell it. -

In 1906, a year before the tipping point of Cubism, the German scholar Wilhelm Worringer completed his doctoral thesis, Abstraction and Empathy. The paper is a study on the form representation takes and the motivation that compels it, a self-described ‘psychology of style’.

The reach of empire had gathered artefacts from countless cultures, tribal and traditional art forms spanning unknown histories whose entirely divergent styles were united only in antithesis to those prevalent in the West. Many artists were drawn to these immigrant lures where likeness to life is abandoned, or more likely – critics claimed – never reached. In their aberrant appearances all familiars are simplified to style or scrawl, all perspective skewed – strained on the one hand or absent entirely on the other as nature is sacrificed to shapes, angles, lines, and patterns. These exotic curiosities, while granted intrigue, were ultimately judged, according to the dominant ideals of the day, against what they were not – that is, natural, accurate – and found inevitably lacking, the result of undeveloped abilities, primitive outlooks.

It is against that judgement Worringer writes, proposing that difference has no basis in lack: these divergent forms shouldn’t be judged as a failure of ability but rather valued as the fulfilment of an entirely different creative intent. The psychology that compels form is driven, he argues, by impulses towards either empathy or abstraction, opposing poles on a continuous spectrum of motivation.

Towards one end, the style that most mimics the real is compelled by the urge to empathise, to connect to life through closer emulation of the forms it provides. This urge to empathy thrusts its bearer into the world, becoming as much an experience of the desiring self as it is an appreciation of the beauty discovered. The world is wild, rich, and given to be found; we are enriched in the finding.

-

Conversely, abstraction sees that same vitality as a chaos, feared and to be tamed; a means of coping with the exhausting phenomena of life by extracting things from their place in space and time, cleaving fragments from a whole, stripping contexts from a world tangled in its own wonders and distilling them to purified line, form, and colour. The world is overwhelming and abstraction is this urge to remake it, to calm its flow, contain its relentless becoming, shut it the fuck up.

I’d not conceived of a spectrum like this until the paper offered it and I took it, making my own erratic from the whole of it. This wasn’t a spectrum inhabited on a point, but one I felt as an entirety, from the doubts that had dead-ended me in a South London studio to the desire that drew me now to Egypt.

-

In images, the rock remains turned to me. In life it looks nowhere.

The rocks I came to photograph will be fashioned as much by the assumptions I arrived with as by the sand in the wind that scours them. Who am I to say what a rock really looks like.

My guide tells me the names of chalk formations I’d rather not know, banalities I’m using the desert to forget: the rabbit, the hat, storks, pharaohs, that kind of thing. I want a rock-form emptied of figures and faces, one that looks like nothing named, that looks like only itself. But since I’m looking it’s already a rock, a uniqueness corralled into a word, and I can’t see the world for them as it is.

-

Here’s what a rock insists, the requirements of an inert but demanding thing: that you face it in silence, as it facelessly faces you. Because it cannot be addressed. It absorbs words like water, mutely.

Is this a presence imagined or remembered.

Here's something I imagine. Rather than the shredded remains of a past, this rock is a gathering up, a consolidation of surface scraped across and together by some unimaginable force – the ground drawn up and guided into form, the only thing on the only surface, the point of all focus and centre of all directions, a stone core at the grinding heart.Can I see it this way because I photographed it that way – turned towards me in silent appeal, the image inviting fictions only words provide – since when I remember, each consolidation of stone has innumerable rivals, each chalk-form being reconfigured in another, repeated further afield than I can see. Hundreds of breaking shapes. And so the many reduce the one, each a variation on the last, each dispel the mystique of the next and the number of possible gods reduces.

-

When I remember…

…pulling words to a fading truth in memories like empathy pulls to the world, or pushing them further to invention, my moments rewritten over until the weight of intervening time sets them like sediment to stone (or at least into text, which is close enough), fixed as memory eroded or the imagined formed. Or remembered form and imagined erosion. Semantics perhaps.

The same difference between intended and invented.

Perhaps. -

You could say a word itself erodes. Falling into obsolescence it becomes known as a fossil word, a cruel metaphor granting dead life but one that likens words to rocks all the same. So then you can picture language as a cliff face and imagine picking through all the fallen words littered at its base; things to be chiseled open, prised apart to measure the aching pace of life. See where their little bones have creaked, their crooked forms unwound to straight, their straight bent round to cursive? See how they clumped together, compressed like sediment in seas of use, how each was the surface of seams running deep and unobserved. There they couple, there they conjoin, and there they cleave apart; each is a testimony, each drags its geology, each splintered up thing a witness to the vestigial histories that formed it, when on our pages and in our mouths it was mauled and chewed around, savoured, whispered, dislocated, swallowed, and spat.

-

The light fades early in the desert. Chalk leaches sun it hoarded throughout the day, casting shadows in the pale nights. I sat looking up in them for hours, their stillness silently absorbing my own.

This kind of night recurs; the staring and the doubt it discovers.Not so dissimilar to writing; this on-screen document a night inverted and as waiting a void to stare into, the few clustered words above and below the present feel like constellations – loosely grouped around a shape they’re named to define, though easily lose.If a gesture scrapes a line through stone, what is that with writing? Why should it be anything with writing. A gesture, unlike an image, needn’t capitulate to words. Though I keep insisting it tries by tuning words to the truth of intention – a truth their basic nature resists, since what are they if not abstract at heart, native nowhere save the very interiors they struggle to convey. Borne about in host bodies with no form of their own, peregrine on the page and tongue, words reveal a voice, as a voice does a speaker, and that exposes me.

It’s unnerving, that words have no surfaces, give no shelter. (Surface – the word itself only serves to reveal the perspective from which it’s spoken, implicate the looking that names it.)

At least, that’s what it feels like to me – like writing erodes a refuge images erect. My images that is, or my work; whatever.

-

In the morning I found crow prints crossing foxes’ in the sand and it was unusual, having seen nothing living since I arrived.

Nothing moving.

No sound, no wind, aimless unravelling clouds, the turn of the earth and the drag of shadows. Contours in the sand. -

Contours in the sand. -

And now, like then, nothing. The clicking of these laptop keys, the ebb of light in the studio, the city quiet enough from here. A plane. A drill somewhere. That stupid ice-cream van. The studio is white; walls, floor, and ceiling. There is a table by one of the windows covered in pieces of chalk, some cut some waiting. There is chalk dust everywhere, there has been for months.

-

I touch a photograph, a contact print I made. Where the negative covered the paper, chalk covers the print and now my fingers, as if the image within was still turning to dust. -

I pick up a lump of chalk, again holding it up, again turning it round. -

Do I choose the lines to cut or allow the rock’s own structure to suggest them? Some shapes lend themselves to those already given while others are forced upon the form in spite of it.

I bring an intention; it’s simply a stone – heavy, all blindly proportioned and awkward in its asymmetry, as misshapen as anything real. Its splintered edges and overhangs assert the rock’s own form, though whether in defiance or as offering, who knows.

Perhaps they suggest my eye and soon blade follow this given edge or that and draw me unawares, the world more coercive than I am.

Or maybe I cut what I want, into and out of it, regardless.

Somewhere between either lies an encounter, of the created and the found, when neither can entirely claim to lead and an end point owes as much to the thing observed as to the one shaping the gaze.

It’s the lure of matter, and it’s also the moment of photography: bringing together the intention borne and the world to bare it.

-

When you flatten all but two dimensions out of life you can cause separate things to align, images doing with space what words can with time.And you can picture a spectrum too – with abstraction one end and empathy the other.

Linear. Like beginnings and ends.

-

Like the rocks of my desert – at least as I write them: chalk torn away in dust by the wind and spun out to nowhere, an erosion that echoes in air its forming in water.

But dust settles and oceans, it seems, rise again. In the timeframes of worlds the flesh of this one – its own rock body and bone – only changes; beginnings and ends are our own inventions, my own habit to break.

My own perspective to force.

-

I think about that spectrum and about how it seems so straight – how the breadth of an intention, of a phrase, of a form, is not so easily placed on a given point between poles, but how it scatters like the real in the remembered – and I picture that line swelling from its centre, spectrum morphing to sphere, and with intention let loose upon it. Extremities of ends become planes of passage, the present moment rolling and unsteady and any perspective as liable to lead, if followed, closer towards, into or through an opposite.

And I think I prefer that. -

I hold the chalk, this time in both hands. A piece breaks away; the whole rock is formed again.

-

There will be a change in the weeks ahead – beginning in the darkroom watching these desert rocks fade into form, chalk finally submerged again but this time in water shallow, red-lit and running gently over the surface they’ve become – as images replace a real I travelled to find, and the photographs taken – by which I mean, like erratics, removed – become a world to pull towards and push against. And in turn, all my gestures of abstraction and connection to those paper worlds – that will leave chalk dust settling over everything for so much time to come – will find their own form, make another world, and this one for words to push into and pull against; one more palimpsest of the found and the made where some kind of sought-for original eludes.

But I don’t know that yet. Not when I’m sitting here among bricks, crossing beginnings out of an already empty journal, and I can only imagine a memory of the desert.

-

Chalkfall in White

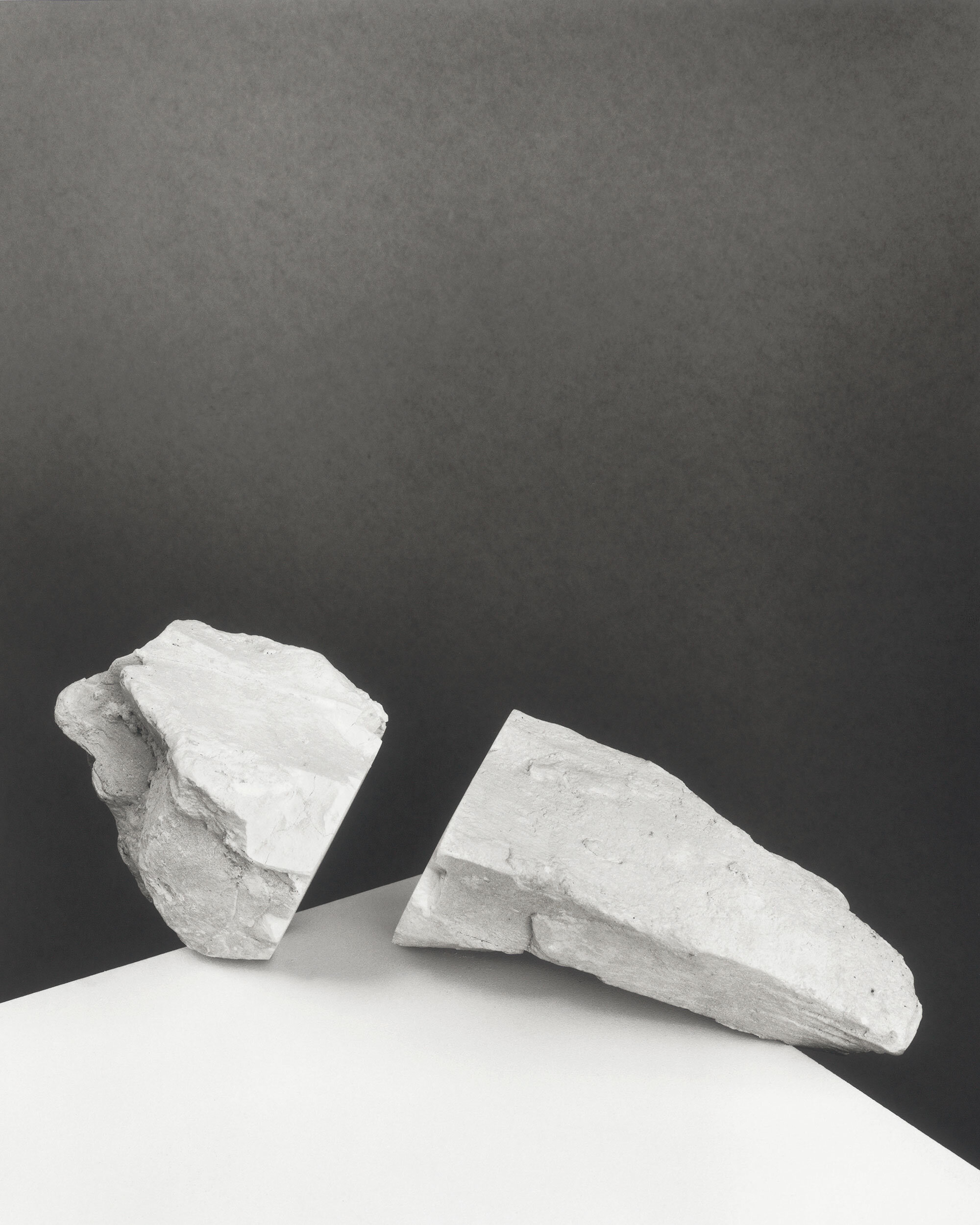

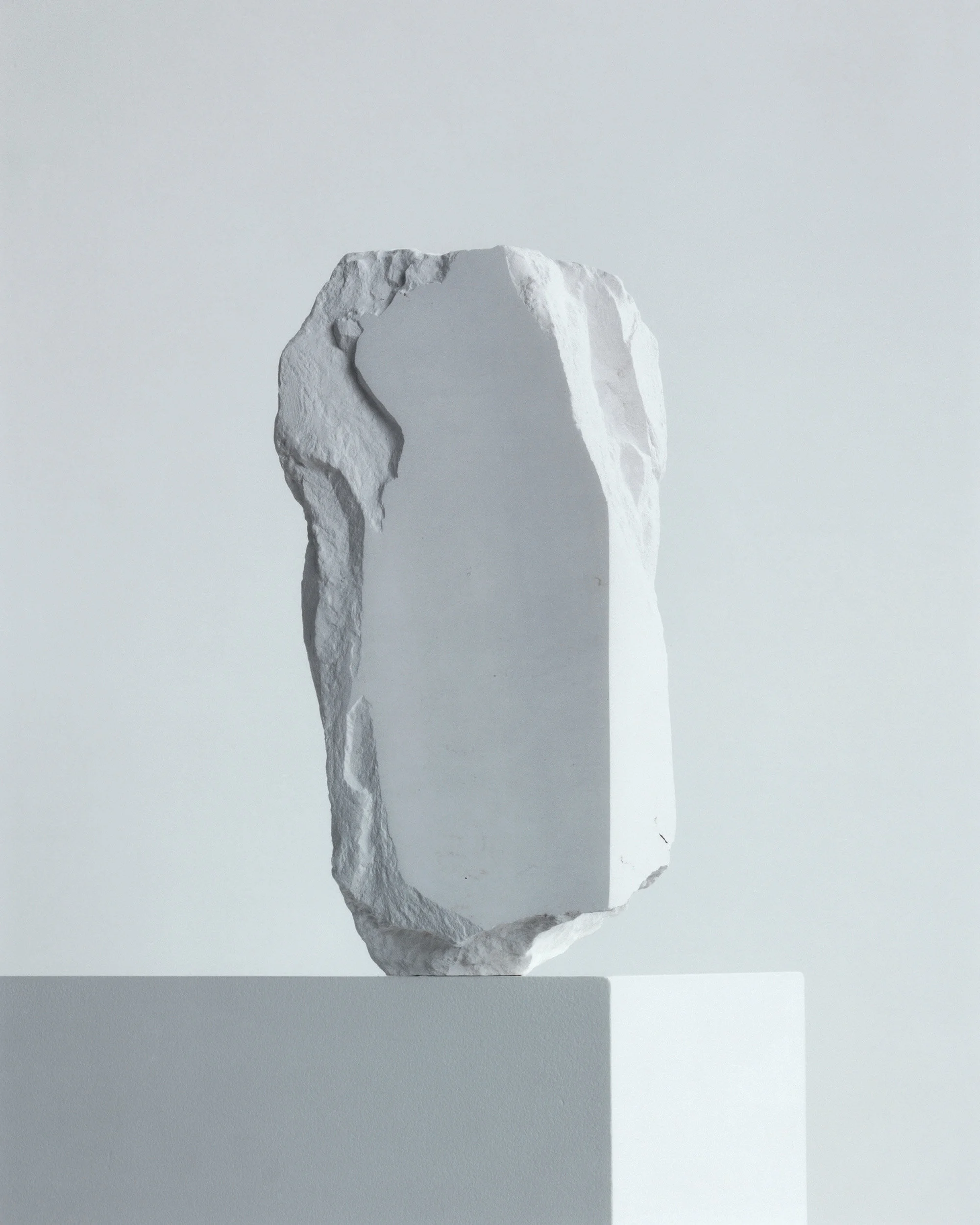

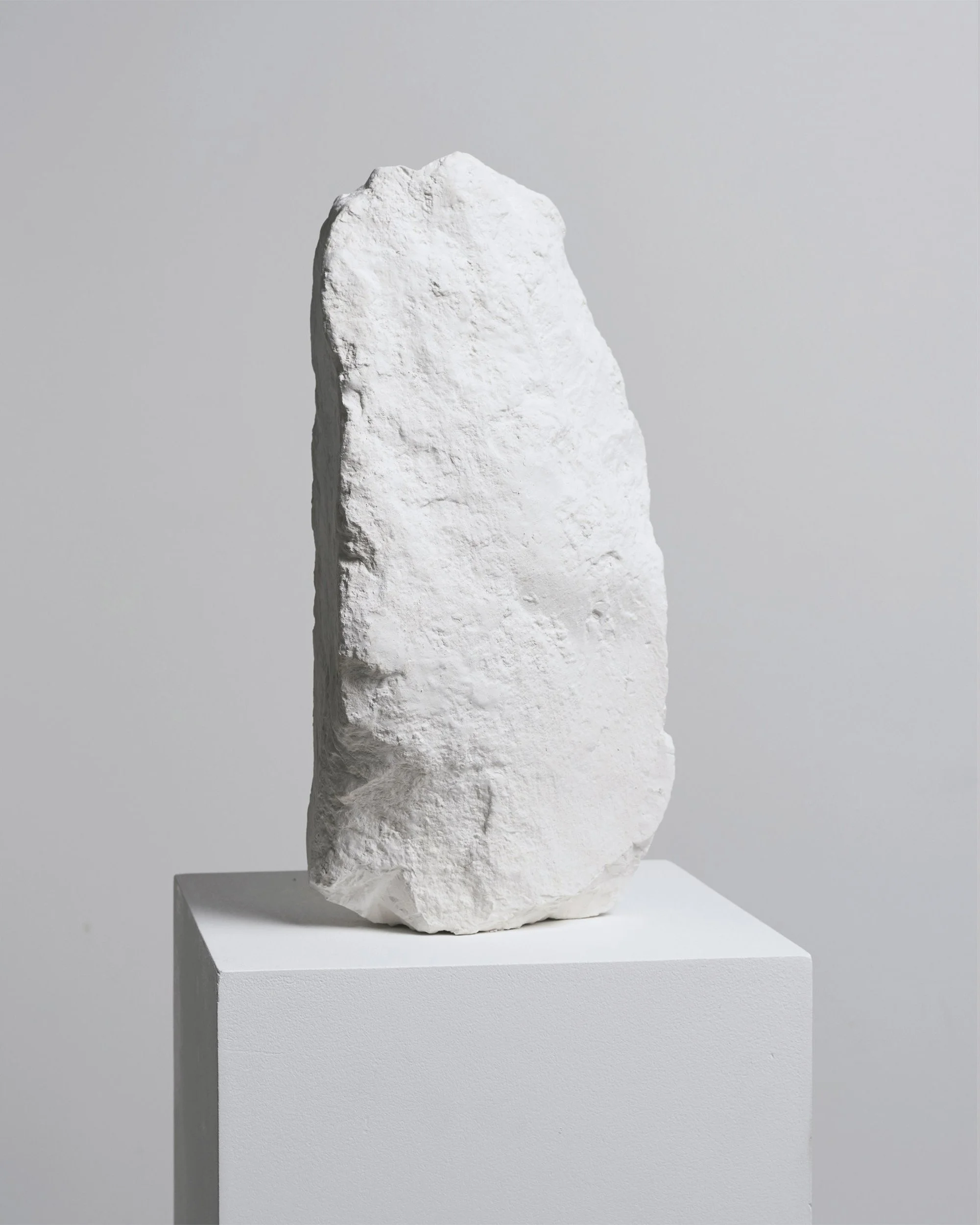

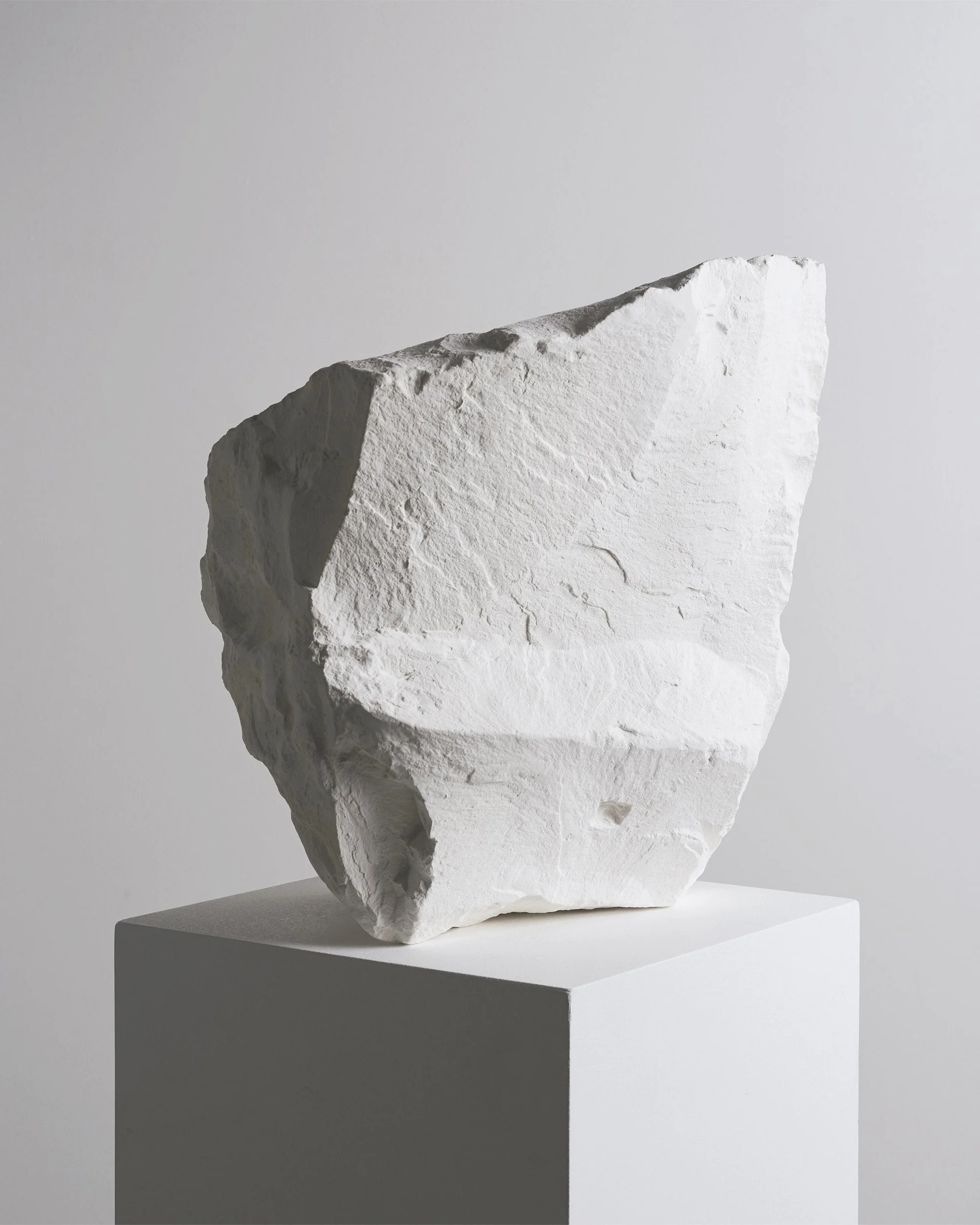

The Erratics comprises two collections of photographs, landscape images (exposures) made in Egypt’s White Desert and studio still lifes (wrest). In exhibition form the sculptural collection (chalkfall in white) is included.

In book form the text work is included.

The Erratics: (exposures), fibre-based prints, dimensions variable, 2014

(wrest) fibre-based handprints and C-type handprints, dimensions variable, 2014-2015

Chalkfall in White, carved chalk, dimensions variable, 2014

The Erratics, published by RVB Paris, 2017